I came across a really interesting article in Publishers Weekly from Emily Midkiff, who is a professor at the University of North Dakota, specialising in children’s literature and literacy. Professor Midkiff claims that children’s science fiction is a missed opportunity for the publishing industry.

I discovered the article when looking for data on whether there is an appetite for middle grade (age 8—12) science fiction. Professor Midkiff, rather handily, had been asking that very question and has conducted her own research. Her findings were fascinating.

Why am I interested?

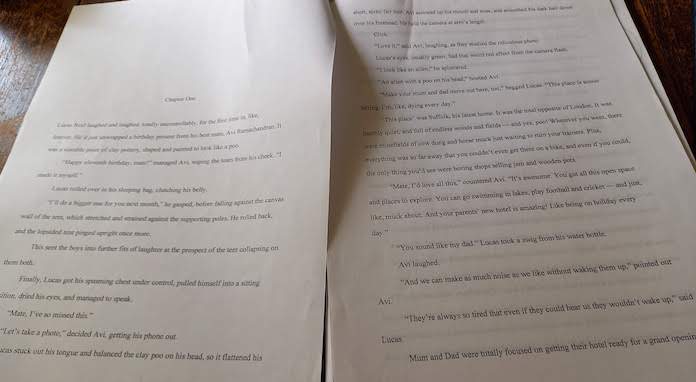

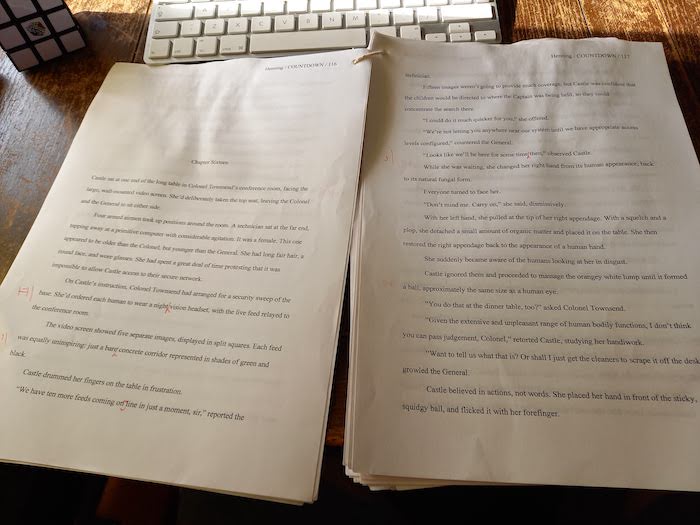

Well, I’m sure you won’t faint with amazement (given that I’ve already written books about teenagers with superpowers and a script for a ghost film) that I also have a great love for science fiction going back to my childhood. I’ve written a science fiction book — yes with space ships and aliens coming to Earth — aimed at the 8 to 12s. I’d very much like to get it published. I’d also like it to sell well. For that, I need a ready market. But is there one? And if so, why the dearth (or Darth?) of children’s sci-fi in bookshops and libraries?

US-based research

Professor Midkiff’s research is US-based, but I suspect it mirrors the UK. She visited elementary school libraries throughout the US and discovered there was a low supply of science fiction books for children, but a high demand. She qualified that statement:

“In each library, only about 3% of the books were science fiction. I expected to see a corresponding low number of checkouts. Instead, the records showed that science fiction books were getting checked out more often per book than other genres. While realistic fiction books were checked out, on average, one to three times per book and fantasy books were checked out three to four times per book, science fiction books’ checkout numbers were as high as six times per book. These libraries may not have many science fiction books available, but the children seem to compensate by collectively checking out the available books more often.”

My own research into children’s publishing trends

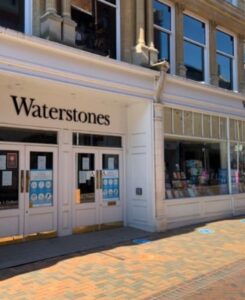

When I was researching my book, I spent some time talking to booksellers in my local Waterstones book shop. The head of the children’s department (who is also a reader for Waterstones Children’s Book Prize) was very helpful. She talked me through what sells, what doesn’t, what the current vogue is, how children shop, what adults buy for them, etc. It hadn’t occurred to me to share those findings before, but inspired by Professor Midkiff’s work, I thought it might be useful for others.

She told me there is not much science fiction out there. Fantasy still dominates. Time travel books seem to be particularly popular at the moment — but time travel in the sense that ‘it just happens by magic’, i.e. there’s no science in the fiction.

She did say, however, that booksellers like to be excited by something different. So if they receive large numbers of fantasy books to put on the shelves and tables, it can often be hard to push one over another. They are always hopeful of something different to get excited about and champion.

She also felt that there is an advantage to shorter books, which are part of an ongoing series. Bigger books tend to leave children bogged down. Better that they enjoy one book, finish it, and then look forward to the next one — as long as there isn’t a long wait until the next in the series is published. You don’t want to start a child on a series, only for them to have outgrown it by the time the next instalment comes out.

Crucially, it is parents who buy books for their kids, although kids say what they want. Interestingly, she had noted how boys, typically, were reluctant to buy a book with just a female protaganist. They didn’t mind girls as a protagonist per se, only that they were much more likely to want the book if there was at least one male protagonist who is approximately their own age.

They are also canny enough to know if the setup of the book doesn’t feel right. So if a ten-year-old boy goes off having adventures one morning without even telling his parents he’s leaving the house, that simply won’t ring true to the reader. There has to be a plausible reason for protagonists to be separated from parents/guardians, if that is what the story requires.

Often, it is the book cover that will sell the book to the kids, which I guess is no surprise. But the cover does also influence parents. If the cover doesn’t look educational, then they try to dissuade the child. Often parents will steer children to the books that they read when they were children (and which no doubt their own parents steered them towards), for example Enid Blyton.

Is there a market for children’s science fiction?

This brings me nicely back to Professor Midkiff’s research. She believes that there isn’t much science fiction available because adults think children won’t be interested in it. Adults bring their own inherent prejudices to the genre. Professor Midkiff may well be right. Adults control what children in that age group read, as the Waterstones bookseller confirmed.

TV and films provide a more level playing field in terms of children’s access to content. The success of Disney’s Star Wars and Marvel output proves that there is an appetite for science fiction stories.

So demand is there, and when the inevitable breakthrough does emerge in the publishing sphere, I’m sure children will be delighted by the rip-roaring, adventurous, sometimes subversive and always mind-expanding stories that science fiction has to offer.

I completed my book earlier this year and have been trying to get literary agents to represent me. Any joy? Not yet. But it’s an ongoing mission. The people who have read it have been very positive. The lady from Waterstones gave me some excellent feedback. She even gave it a trial by fire by reading it to her young daughter, who’s genre preference is unicorns. The result: She actually liked it. Thank the maker!!

Writing this book was born from a deep desire to recreate the joy and wonder that I vividly remember from reading such books in my own childhood. Back then, I’d immerse myself in stories that took me to strange new worlds and made me think very differently about the one in which I was living in (which may or may not be the same one as everyone else??).

I’m desperate to continue the story, so I’m hoping that the tipping point in publishing is reached very soon and there’s a more obvious and hungry market for middle-grade science fiction. It may not be publishing’s final frontier, but it is long overdue to be re-discovered.